March 6, 2012

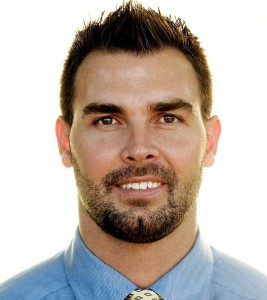

Bret Contreras Interview

Today’s post is an interview I conducted with uber trainer Bret Contreras. If you’ve read this blog over the past couple of years, you’ll know that I hold Bret in highest regard; someone I’m proud to call a friend and colleague. Not only does Bret have a terrific grasp of the research, but he is able to harness this info and apply it in highly innovative ways that few can match. This is the essence of evidence-based practice and no one does it better. Pure and simple, he’s one of the preeminent fitness professionals in the world.

Bret has just come out with a terrific monthly research review that synthesizes the current research from a practical perspective. I ask him about this as well as a number of other fitness-related topics that I’m sure you’ll find of interest.

BJS: Tell us a little about your background in the fitness field.

I’ve been weight training and reading about fitness for 20 years now. Like most in the fitness industry, I started accumulating tons of workout partners in my teens. This gradually evolved into personal training on the side until finally moving to full time training and strength coaching. Eventually I opened up my own facility which I had for a couple of years and then I switched to full time writing and researching.

No matter how busy I am, I always make sure to keep a few personal training clients so I don’t become too theoretical and esoteric like some researchers. Training real clients and having discussions with fellow strength coaches, trainers, and therapists keeps me grounded and humble.

BJS: You’re often referred to as “The Glute Guy.” How did you come to get this nickname?

To make a long story short, I was talking to legendary strength coach Martin Rooney a few years back at a Perform Better seminar and was discussing my EMG findings on the glutes. He jokingly mentioned that I give myself a name and threw out “The Glute Guy” as a suggestion. I liked the sound of it and went forth with the nickname, and now it has stuck. I’m very comfortable being known as The Glute Guy as I believe that the gluteus maximus is the most important muscle in sports since it’s heavily involved in running, jumping, cutting, and twisting – all extremely powerful movements. In my opinion it’s also the most important muscle for increasing women’s sex appeal.

BJS: What is your training philosophy?

I could write an entire essay on this, but it depends on the client and the goal.

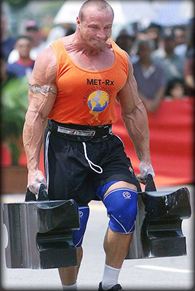

For sport training, I believe that 80% of the potential gains from strength training come from “general” big lifts such as squats, deadlifts, bench press, bent over rows, military presses, and farmer’s walks. I believe that the big lifts can and should be modified to be more joint-friendly or replaced by biomechanically-similar exercises for lifters who don’t tolerate the big lifts very well. For example, front squats, hex bar deadlifts, incline presses, inverted rows, and neutral grip dumbbell military presses are suitable alternatives which are generally safer but will yield nearly identical adaptations.

I believe that the remaining 20% of potential gains from strength training come from exercises which are chosen by analyzing the specificity of the sport and position. The most underutilized principle of specificity is the direction of the forces in sport. Force vectors need to be mimicked in strength training to maximize the transfer of training. There are typical strength exercises that help bridge the gap between weight training and sport, such as hip thrusts, back extensions, Bulgarian split squats, cable hip flexion, cable woodchops, and JC band presses. Explosive lifts such as Olympic variations, jump squats, kettlebell swings, slideboard lateral slides, and medball throws; as well as towing exercises such as sled pushing bridge the gap as well. I believe that these special exercises put the finishing touches on a well-balanced general routine and significantly enhance the transfer of training.

For hypertrophy training, I believe in getting people really strong in a variety of exercises in a variety of rep ranges from a variety of angles while incorporating a variety of methods. How’s that for being vague? I’ll elaborate.

Let’s say I was aiming to achieve maximal pectoral hypertrophy for an experienced male client. In this case I would seek progressive overload in barbell and dumbbell bench and incline press variations for low to medium reps. I would incorporate targeted movements such as flat and incline fly and crossover variations for medium to high reps. From time to time I’d throw in weighted dips and push-ups (assuming they were well-tolerated by the client) for medium reps. I’d rely on traditional methods such as straight sets and pyramiding, in addition to utilizing neural overloading techniques such as the rest-pause method and pumping techniques such as the constant tension method with short rest times in between sets.

BJS: Do you believe in periodizing programs?

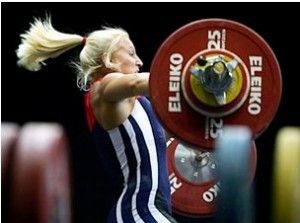

Of course I do, but not in the same manner as most coaches. There’s an Olympic Weightlifting coach out of Las Vegas named John Broz who sticks to six exercises year in and year out. His athletes are far more explosive than 99% of those who train with other coaches. They get really good at squatting and front squatting, cleaning and snatching, and power cleaning and power snatching, and their routines don’t vary from week to week and year to year. There’s something to be said for sticking to the basics and keeping it simple for strength and power gains, and Broz clearly demonstrates that fancy periodization is not a requirement for impressive training results.

However, it’s of utmost importance to keep clients and athletes injury-free. For this reason, I wouldn’t feel comfortable sticking with Broz’s approach, though I recognize its efficacy in terms of performance gains.

Currently I don’t train many clients but I’ll discuss some things that have worked well for me in the past as well as over the past year with some of the clients I’ve trained. First, I periodize according to skill level. I’ve learned much from Gray Cook over the years and think it’s imperative to focus on developing sound fundamental movement patterns which requires ideal levels of mobility, stability, and motor control. All clients and athletes need good squatting, hinging, and bridging patterns, as well as single leg and lumbopelvic stability. Corrective exercises should be utilized up front where necessary to fast-forward progress.

Once good technical form is reached on the big lifts, correctives are placed on the back-burner by moving them into the general warm-up, and the primary focus shifts to progressive overload. Getting stronger at the big lifts through a full range of motion without compromising perfect technical form is the name of the game. Once sufficient strength is reached following many years of strength training, main exercises should be rotated frequently and explosive repetitions via the dynamic effort method become more important.

Second, I sometimes periodize by targeting the weakest range of motion along the strength curve. For example, lifters who seem to fail down low and display disproportionately low flexed-range hip extension strength would be prescribed full squats, deficit reverse lunges, good mornings, and deficit deadlifts, which are all very hard in a deep position of hip flexion. Conversely, lifters who seem to fail at lockout and display disproportionately low end-range hip extension strength would be prescribed high box squats, rack pulls, back extensions, and hip thrusts, which target mid or end-range hip extension strength. I usually prefer to blend these movements together during programming but I’ve achieved great results with several clients by using this methodology. In fact several months ago I put 35 kgs (around 77 lbs) on a guy’s deadlift with this approach in just four weeks.

Third, from time to time I periodize by alternating clients between higher frequency approaches, higher volume approaches, and higher intensity approaches. Though this is a very common approach to periodization, I do it differently than many coaches as I switch things up more drastically than just tinkering with sets and reps – I’ll vary the exercises, manner of execution, and special methods as well. For example, during the high frequency phase I’d keep things simple and stick to the basics. During the high volume phase I’d employ bodybuilding techniques such as drop sets. And during the high intensity phase I’d employ HIT techniques such as breathing squats.

Fourth, I periodize by choosing new goals each month for my clients based on their input. One month we might try to set a record on maximal deadlifts. Let’s say a male client can deadlift 365 lbs, I may design the program around trying to get him to reach 405 lbs by the end of the month. Perhaps the individual wants to lose 5 lbs of fat for the month; I might add in 10-15 minutes of HIIT or MRT at the end of the session.

Fifth, I often periodize by utilizing an undulating (non-linear) approach, for example during a high frequency phase I might go with heavy weight for low reps on Monday, light weight for high reps on Tuesday, moderate weight for explosive reps on Thursday, and moderate weight for medium reps on Friday.

So there are a few ways in which I periodize programs. One approach to periodization that I don’t like is the classic (linear) approach that has you tapering down on rep ranges over time. I don’t like this method as individuals seem to get really good at whatever rep range they’re training at the expense of losing strength in the other rep ranges. For this reason I believe that every week should include some heavy low rep work, moderate medium rep work, and light high rep work for maximal efficacy. I do have some colleagues who have achieved good results using this approach so I recognize that it seems to work well for certain folks.

I should also mention that I am a big fan of programming according to instinct/gut feeling, though I don’t feel that this is a true form of periodization. Whether you call it auto-regulation, Cybernetic periodization, instinctive training, or biofeedback training, it’s all similar. You have a clear agenda and specific goal in mind for when your client enters the weight-room, but you tinker with the program on the fly based on verbal and non-verbal feedback from the client. I believe that all good programs rely heavily upon auto-regulation as it’s impossible to predict the precise psychological and physiological disposition of the client on a regular basis as there are just too many factors at play.

BJS: I know you’ve worked a lot with EMG. Do you consider it a useful instrument for studying biomechanics?

Hell yeah I do! Anyone who says otherwise hasn’t worked with EMG and doesn’t regularly read research. Strength & Conditioning writers are great at coming up with new ideas and new theories – in fact they’re the best. Sometimes these theories end up being right, but often the theories are either incorrect or incomplete. Researchers and sports scientists use various tools to learn more about the neuromuscular system and test hypotheses, and EMG is just one of these tools.

EMG is great because it measures the electrical activity in muscles; a measurement of the nervous system’s intent to fire the muscles. This gives us a reasonable measurement of muscle force (especially during isometric contractions and when non-fatigued) which is related to mechanical tension and ultimately, hypertrophy.

Like any tool, EMG has some shortcomings, but many of the shortcomings can be ameliorated, for example you can use multiple channels of EMG (i.e. using multiple electrodes on a particular muscle) during testing to cover more surface area and test more regions of the muscle. I like that EMG can be lined up with motion capture to analyze EMG timing relative to motion. EMG can be incorporated into muscle modeling along with force plate data and inverse dynamics to help predict joint torques, spinal loading, and muscle forces. Spinal biomechanist Stu McGill utilizes this approach in his experiments.

I learned so much valuable information when I conducted my extensive EMG experiments. I’d hook up 4 electrodes to various regions of muscles and perform tons of different exercises to see which movements activated the various muscles and regions of muscles best. Many times the experiments validated what I already knew through practical experience, but a few times I was very surprised at the results. However, after pondering the results and analyzing the biomechanics of the movements, the EMG findings made perfect sense.

My favorite aspect about EMG is that it’s the only tool that I know of that gives us numerical data to give us some idea as to muscle force. MRI and ultrasound are nice but they don’t provide numbers. Until we have a more practical way to measure actual muscle force, to me standardizing EMG to MVC is the way to go.

Many of my researcher colleagues and strength coach colleagues are quick to dismiss EMG because of various reasons and I always listen to their rationale. But usually I think their rationale is overly-critical and unfair. There are indeed limitations, but it’s the best tool we’ve currently got for seeing which exercises work a particular muscle or muscle part the best. Sure we can utilize other methods, such as MRI (there’s even a newer MRI technique called “STIR” which examines muscle damage following a workout), ultrasound, biomechanical analysis, “feeling the burn” during exercise, palpation, and simply doing a bunch of sets and seeing where you’re sore the next day, but EMG gives us actual numbers to use for comparison.

Bodybuilders have long claimed that you can perform specific movements to target a particular area of a muscle. Sports scientists were skeptical, but EMG has provided much evidence for their claims. Bodybuilders were right about the delts, traps, pecs, lats, abs, glutes, quads, hams, and calves; muscles don’t get worked uniformly across the various fibers and specific exercises can be used to strengthen or hypertrophy a particular region. This is useful for functional purposes and sport, for bodybuilding purposes, and for rehabilitation purposes. We’re now learning that the nervous system is skilled at determining which parts of the muscles have the best leverage at a particular range of motion and it fires those regions when appropriate to produce efficient movement – this has been coined “functional differentiation.”

Just recently EMG was used to dispel the “corset hypothesis” that most physical therapists and strength coaches subscribe to; we learned that the transverse abdominis doesn’t contract uniformly during unilateral limb movement. There are many excellent uses for EMG and when used by a skilled practitioner who understands its strength and limitations, it’s incredibly valuable.

BJS: You have a new product out that I know you’re quite excited about. Tell us about it.

I sure do. It’s a research review service that I started with my colleague Chris Beardsley – someone who I respect immensely. Beginner coaches and lifters need to spend time in the trenches gaining experience under the bar and working with other people. They don’t have time to sift through the research, and even if they did have the time, chances are they don’t have access to the journals.

Yet every young and advanced athlete, lifter, trainer, therapist, and coach could benefit considerably by receiving a monthly report that summarizes the latest findings in strength & conditioning, biomechanics, physiology, and physical therapy. This is exactly what Chris and I will do each month; we’ll pick out the 40-50 best articles for the month with a good blend from each category and summarize and email them to you in a nice PDF format.

Think about it – the President of the United States has advisers that hand him reports so he can stay informed. I’d like for you to feel like the President each month, so let Chris and me do the hard work for you so you can stay abreast of the literature and have an edge on your competition without taking up too much of your precious time.

For just $10/month you can be in the know by subscribing at www.StrengthandConditioningResearch.com. I can’t begin to tell you how much more intelligent and informed I am as a coach following a year of intensive studying and researching. It is my hope that strength & conditioning enthusiasts will take my word for it and subscribe as I can’t imagine anyone regretting it – so far all the feedback I’ve received has been very positive. Thanks for the interview Brad – I appreciate the opportunity!

Check out Bret’s blog at: Bretcontreras.com

Check out Bret’s review publication at: StrengthandConditioningResearch.com

7 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)

Great interview! Nice to see this consolidation of information from the brain of Bret 😀

Good luck on the new Research product – sounds solid!

Comment by Mitch — March 6, 2012 @ 9:55 pm

It’s really a great and helpful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

Comment by biofeedback therapy — March 6, 2012 @ 10:31 pm

I’ve already subscribed and am looking forward to future issues. Although I did read a lot of research when I was in college, it definitely made me realize I’m more of a technician in terms of what I like in the field. So having this as a resource is great. I’ve read Bret’s blog for a while and am glad he’s put something of this caliber out. Thanks for the great interview!

Comment by Richard — March 7, 2012 @ 8:30 am

Thanks for the kind words Mitch and Richard!

Comment by Bret Contreras — March 14, 2012 @ 5:44 am

[…] week my buddy Brad Schoenfeld interviewed me HERE. I felt that this was a very good interview so please give it a read if you haven’t […]

Pingback by Bret Contreras » Random Thoughts — March 14, 2012 @ 6:15 am

Nice interview, Brett!

And congrats on your new product. Something which was badly lacking in our industry!

Comment by Anoop — March 14, 2012 @ 10:09 pm

gluteus maximus workouts…

[…]workout911.com » Bret Contreras Interview[…]…

Trackback by gluteus maximus workouts — April 1, 2012 @ 7:43 am