Search Results

March 29, 2014

The Best Muscle Building Workout!?

Admit it. You’ve probably been lured into reading a magazine article with headline such as the one above. These types of claims are the norm rather than the exception in the muscle rags and fitness websites. And for good reason: the promise of a holy grail of workouts that will maximize your muscle development is an enticing prospect to say the least.

Problem is, no such routine exists.

It’s essential to realize that the response to resistance exercise is highly individual. Remember that research simply reports the means (i.e. averages). So if a study reports muscular growth after a given protocol as say 10%, you can bank on the fact that some subjects grew a lot more and some a lot less than 10%. Thus, you can’t simply extrapolate that you, or a client of yours, will achieve similar results to the reported mean.

Nowhere is this better illustrated than in a recent cluster analysis study by Bamman et al.. Sixty-six men and women performed supervised lower body exercise (squats, leg presses, and leg extensions) 3 days a week for 16 weeks. Training was carried out in typical bodybuilding-type fashion that included 3 sets of 8-12 reps for each exercise. At the end of the study, subjects were grouped by their hypertrophic response: The top 17 subjects were considered extreme responders. Their muscular gains averaged ~58%. Pretty awesome, right? The middle 32 subjects were considered moderate responders, with muscular gains averaging ~28%. Still pretty good, although well below the extreme responders. Here’s the kicker: the bottom 17 subjects saw, get this, NO significant gains after 16 weeks or consistent training. Zilch! Again, all subjects performed the exact same program but, as noted, saw widely disparate results. Based on the research, genetic factors are highly responsible for these differences, including the expression of various proteins (such as IGF-1) as well as satellite cell population. Lifestyle factors undoubtedly play a role as well.

Now the fact that people respond differently doesn’t discount that there are certain principles that should be inherent in any routine designed to maximize muscle-building. These include:

• Vary the loading strategies: Using different rep ranges (i.e. heavy, moderate and light) will ensure that you stimulate the full spectrum of muscle fiber types in a fashion that produces maximal growth. Recent work from my lab shows that light loads are suboptimal for fully activating the highest threshold motor units, but they may be superior for targeting the type I (endurance-related) fibers.

• Train with high volumes: There is compelling evidence that a dose-response relationship exists between volume and hypertrophy. Although a single set to failure can produce substantial increases in muscle growth, multiple sets are needed for maximal gains.

• Perform a variety of exercises: Muscles frequently have varying attachments and individual fibers are often compartmentalized so that they are innervated by different nerves. Research shows that a single exercise is not sufficient for maximizing whole muscle growth. To ensure complete muscle development, you need to have sufficient variety of exercise selection that takes into account basic applied kinesiological principles as outlined in my recent T-Nation article.

• Employ some sort of periodization scheme: This simply means that you need to manipulate variables over time. In particular, volume and training frequency should be varied over the course of training to prevent plateau. Ideally, volume/frequency should culminate with a relatively short training cycle designed to produce functional overreaching followed immediately by a period of deloading/active recovery. This will help promote a supercompensatory response that maximizes muscular gains. The process doesn’t have to be complicated; there are endless ways to go about periodizing a routine as long as you proceed in a logical fashion.

Given these basic tenets, it is essential that you take individual differences into account when designing training programs. There are no cookie-cutter prescriptions for getting big. For those familiar with my book, The M.A.X. Muscle Plan, you’ll know that I reinforce this concept repeatedly throughout the text. That’s why I refer to the book as a “template” for success; optimal benefits can only be achieved by customizing the program to your own personal needs and abilities.

Bottom line: There is no “best” muscle-building program; only a best program for a given individual.

December 4, 2013

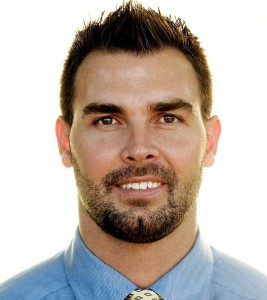

Interview with Tom Venuto

Tom Venuto is one of the good guys in the fitness field.

For those who don’t know of his work, Tom is a former natural bodybuilder who turned a passion for getting fit into a passion to help others optimize their fitness goals. He is founder of the popular blog, Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle and is author of of a number of succesful books. What I admire most about Tom is his balanced, evidence-based approach to exercise and nutrition (as you will know doubt see in the ensuing interview). He is a student of the science as well as an in-the-trenches practitioner. This combination of experience and insight makes him one of the most sought-after practitioners in the country.

I’ve known Tom personally for many years and I’m pleased to have interviewed him about his new book, Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle: Transform Your Body Forever Using the Secrets of the Leanest People in the World, which will be released next week.

BJS: Thanks so much for consenting to do this interview Tom. I’ve always been impressed with your down-to-earth, scientific approach to fitness. For those not aware of your accomplishments, can you give a brief rundown on your background?

Thank you for the opportunity Brad. I’ve been training for over 30 years nonstop. I got my undergrad degree in exercise science and was a competitive bodybuilder and personal trainer for almost 15 years. Today my full time job is coaching people online through our Burn the Fat community and I’m also fitness writer. I blog at Burn the Fat Blog.com and I’m the author of two books on fat loss including The Body Fat Solution and Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle.

BJS: Your new book, “Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle,” was previously published as an e-book. What is different about this book from the previous edition?

The original ebook was first published in 2003. The theme of the new version is the same – the book teaches regular people how to use the nutrition, training and psychology strategies of bodybuilders and other physique athletes – to achieve their own goals. In a decade, a lot of new research emerges and if you stay on top of your game, you grow and evolve as a coach and communicator. I believe it’s important to share the most up to date information and best practices with your readers, in the simplest terms possible to help the most people. So the book has been re-organized, revised and updated with 25% new material including new chapters and a new workout program.

The biggest change I’ve seen over the last decade, which is reflected in what I write, is not a single new diet breakthrough or the discovery of one superior training technique – it’s quite the opposite – it’s how we’ve learned that there is more than one way to skin a cat. Does low carb work? Yes. Does high carb work? Yes. Does 6 meals work? Yes. Does 3 meals work? Yes. Do plant based diets work? Yes. Do meat based diets work? Yes. Does a full body workout work? Yes. Does a body part split routine work? Yes. And yet, this is the hardest thing for the dichotomously-thinking human brain to grasp because it seems contradictory. Fueled by marketing, personal ideologies and the guru culture, most people want to keep believing there’s only one true way. But it doesn’t exist. We need to focus more on the vital few fundamentals that apply to everyone, worry less about the trivial stuff and craft a personalized plan we can live with.

In that spirit, the book stays focused on the same principles and it’s still structured and by the numbers, but it’s more flexible than ever before, allowing for the kind of customization that accommodates an individual’s lifestyle and preferences. It’s also accessible to people who aren’t bodybuilders or scientists. More than ever, Burn the Fat, Feed the Muscle looks at both what the research says and what the real world says – or as you have eloquently said – it’s about the art and the science.

BJS: You discuss how exercise and nutritional routines should be customized based on body type. Can you explain why?

I would describe my philosophy as being more about customization to accommodate everything unique about each individual than about body type in a genotypic classification system sense. Bodybuilders have been fascinated with body types for years – you see somatotyping mentioned in almost all the classic muscle building books – and I do explain those body types in my book too, but I then explain the limitations of the classic Sheldon system, and go beyond it by describing the new phenotypic view about somatotypes.

Mainly, it’s a simple matter of “know thyself.” Know your tendencies biologically and behaviorally, know your goals, know the lifestyle you want to live, and then that helps you customize your workouts and nutrition.

Some of the explanations for body types are so simple, they’re usually overlooked, but becoming conscious of them can be very helpful. For example, what is an ectomorph really, beyond a certain frame and bone structure? Most people think it’s a guy who inherited a really fast metabolism so he burns everything off and never gets fat. “Lucky him” the endmorphs say. But most research says that inter-individual variation in metabolic rate, while it does exist, it’s pretty small. When you look more closely, you see the ectomorph is a person who has extremely high levels of NEAT (non exercise activity thermogenesis) and simply never stops moving. He may also have characteristics that influence him to eat less. Both of these can be genetically influenced. The reverse is true about the endomorph.

I don’t think there’s enough science to put legs under any body typing system in a way that you could just give everyone a quiz and then say, “You’re an X body type so follow program X and you’re a Y body type so follow program Y.” But there are biological and behavioral differences in people that affect how much energy they burn and how much they consume. I also believe there are degrees of carbohydrate intolerance. How much that influences differences in body composition is pretty speculative, but surely some people don’t fare as well on health markers with high carb diets and that’s easy enough for each person to test and prove for themselves. It’s also fair to say that the carb prescription for sedentary people is quite different than it is for athletes. So I think knowing yourself and customizing everything could be seen as a kind of “body typing” I simply don’t stretch it too far beyond that.

BJS: What’s your opinion on calorie counting? Is it really necessary?

Calorie counting is not necessary, but if your goal is fat loss, having a calorie deficit is necessary. The important distinction that a lot of people miss is that there’s a big difference between saying “you don’t have to count calories” and “calories don’t count.” That might sound like the same thing, but it’s not. Lots of people lose weight without counting anything. But that’s because they’ve still achieved a calorie deficit. Whether you count calories and you’re in a deficit or you don’t count calories and you’re in a deficit, the end result is the same – you lose fat.

In a perfect world, we could argue that it really is ideal to follow an eating plan that automatically produces a deficit without you counting calories. It’s like what Brian Wansink said, “The best diet is the one you don’t know you’re on.” The problems are: 1. That’s easier said than done for a lot of people. 2. Many “experts” claim calories don’t matter for weight loss – that it’s only about hormones or eating special foods. Ironically, many diets that prescribe the avoidance of certain “evil fat storing foods” and the frequent consumption of certain “magic fat burning foods” are simply tricking you into eating less. Again, that’s not necessarily a bad thing, except when the “magic” food concept is presented as a gimmick or when “evil” food avoidance becomes dogma and that often turns into real food phobias or even eating disorders.

My approach is to start out building meal plans by the numbers – know your calories and macros – because doing the numbers at least once in your life is an education about nutrition you can’t get any other way. If you’re stuck at a plateau – do it by the numbers as well. You may be shocked at how much you are underestimating caloric intake.

After you’ve done the counting thing for a while, it becomes second nature or “intuitive” if you prefer that word, and you don’t have to do it anymore. But the way I see it, “intuitively” eating the right amount of calories is not something that comes naturally in our modern, temptation-filled, sedentary world today, it’s something you learn and earn through an education and conscious mastery process. Anything else and you’re just guessing, and if you guess right, I would call that luck.

BJS: How important is the macronutrient ratio in optimizing body composition?

Getting a proper balance of protein, carbs and fat is important, but there’s no single macronutrient ratio that’s best. There is nothing wrong with one ratio like 40-30-30, for example, which became very popular through a best-selling diet program. But any reasonably balanced nutrition plan that provides adequate protein, essential fats, fiber and micronutrients, and doesn’t tilt to such extremes that anything essential is pushed out, can be chosen based on personal preference.

I also have no problem setting up meal plans by sensible macronutrient ratios – it makes it easy for me to visualize and conceptualize my plate and food portions. If you use the macro ratio method though, you do have to be conscious that you are using relative figures and one ratio also won’t apply across hypo-, hyper- and iso-caloric meal plans. In a calorie deficit (hypo-caloric) it’s reasonable and prudent to hold protein constant if carb calories are reduced and therefore the ratio of protein goes up though the grams may stay the same.

I would focus especially on hitting the protein goal and checking your quota in grams relative to your body weight, goals and training status, based on the current evidence for optimal protein intakes.

BJS: From a training perspective, how often do you recommend varying the exercises performed?

Short answer: More often for advanced trainees, less often for beginners; more often for bodybuilders seeking hypertrophy and symmetry; less often for pure strength goals. But everyone benefits from exercise variation.

A lot of strength coaches say that your body adapts to the repetition range quicker than an exercise and I think there’s a lot of truth to that. For example, you’re likely to plateau after weeks of squatting sets of 5 or sets of 10 while progressing the weight linearly. But if you implement heavy and light days with different rep brackets, or even three rep brackets, and you vary the intensity of effort too, you’re likely to be able to milk that cycle on that one exercise longer and then continue to get the benefits of one superior exercise.

But with that said, there’s no one exercise that can completely develop every angle, every aspect of every muscle. This is especially important for bodybuilders. A lot of bodybuilders at the advanced level say they feel like they start adapting to an exercise in as little as 3-5 workouts. At the advanced level, I think it makes a lot of sense to change at least some, if not most, of your exercises monthly, sometimes even sooner, and when staying with the same exercise, working the different rep ranges with varying loads as mentioned above. It’s also worth mentioning that boredom is a program killer for a lot of people and mixing it up keeps things interesting.

BJS:Any supplements you feel are particularly worthwhile for muscle building and/or fat loss?

No doubt there are a small handful of supplements with evidence supporting their benefits, some measureable and noticeable. But I’ve never been a big advocate of supplements. Most of them don’t work at all and the few that do are usually terribly oversold, especially in the advertisements.

To be honest, I have a hard time understanding the insatiable desire people seem to have to “take something” considering that supplements are never the make you or break you factor – they’re more like the slight edge. Let me also say that there are very very very big bucks being made in this industry, so always factor that into your buying decisions. Demand strong evidence before buying anything and be extremely careful buying from a company you don’t know anything about. Better: Buy from well-established company you trust, with a human you can contact.

I’ve used creatine before with noticeable results, mainly in workout performance (strength increase), but it doesn’t bother me one bit to train without it. I would use it again and possibly other products if I were in a competitive situation.

I do like protein powder because I use it as food – or as a recipe ingredient. I stir it in my oatmeal, or I mix it with peanut butter and greek yogurt (you gotta try that with chocolate protein – it’s like dessert). And I also appreciate a good smoothie, tasty meal replacement or protein shake recipe, especially if my diet is restricted – It feels like a treat.

BJS: Finally, where can people read more about you and find your book?

My home base on the web right now is my blog – Burn the Fat Blog and our online community where I coach and support our members is Burn the Fat Inner Circle. You can find my on facebook/burnthefat and twitter/tomvenuto. The Burn the Fat Feed the Muscle book is now available in a hardcover and audio version on amazon, barnes and noble and everywhere else books are sold.

October 15, 2013

Fitness Podcasts

Happy to report that I’ll be doing regular fitcasts with my brother-from-another-mother, Bret Contreras, which we somewhat unoriginally call the B & B Connection (what’s in a name, right?). We’ll be discussing the practical application of research on a variety of fitness topics, objectively delving into some of the more controversial issues that currently exist. Each fitcast will be limited to 30 minutes (translation: we’ll cut right to the meat of the topic without any fluff).

Our inaugural fitcast covered the mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy. We explored my review paper, The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training, with specific emphasis on the roles of mechanical tension, metabolic stress, and myodamage on muscle development. For anyone interested in maximizing their muscle mass, this fitcast will serve as a primer to help with optimizing exercise program design.

In our second fitcast we tackled the hotly debated topic of high-intensity resistance training (HIT). For those who don’t know, HIT is a catch-all for single-set training. The discussion was spurred by a recent research study showing that single set training was equally as effective as multi-set training in improving measures of upper body strength. As is often the case, however, the devil is in the details. What does not get mentioned in the abstract (or anywhere in the discussion, for that matter), is that the “single set” group actually performed one set of three exercises for each muscle group. Given that the subjects trained three times per week, this amounted to nine sets per muscle per week. Not exactly what I would consider a “single set” routine, and certainly not consistent with what HIT pioneers such as Ellington Darden have prescribed as optimal for muscular adaptations. Understand that this by no means invalidates HIT as a potentially viable approach. As Bret and I discuss, the issue on training volume ultimately comes down to your personal goals. I highly encourage you to give this one a listen and let us know your thoughts on the topic.

Suffice to say, I’m very much looking forward to our future B & B fitcasts. Stay tuned.

In addition to my collaboration with Bret, I’ve been interviewed on a number of other sites recently. Here’s a rundown of each:

embedded by Embedded Video

Okay, gotta get back to work on my dissertation now. In the meantime, hope this provides you with enough listening enjoyment for the time being!

Brad

April 27, 2012

An Interview with Nick Tumminello

Nick Tumminello is not only an excellent trainer, he’s one of the real good guys in the fitness field. But what really impresses me about Nick – in addition to his innovative approach to training – is that he’s never afraid to speak his mind and challenge accepted dogma on a given fitness-related topic. You may remember that I interviewed Nick here a little over a year ago. Well, Nick has just come out with a new DVD on single leg training and it just so happens he has some interesting things to say on this subject and a few others. So without further ado, here’s the uncensored interview:

BJS: Musclemag recently featured you for your work with bodybuilders in this awesome 7 page spread. Congrats! How did this come about?

NT: I’m always grateful that I get to write articles for major fitness magazines. But, to have a major magazine do an article about me… man is that a huge professional honor! Especially in MuscleMag, which has been of one my favorite magazines since being teenager who was into lifting and trying to “get swole” 🙂

The article feature came about because I’ve been writing articles for several of the RKP magazines: Oxygen, Maximum Fitness, REPS! and MuscleMag. The editors of MuscleMag know me as a guy who’s always full of scientifically-inspired and athlete-approved ways to upgrade classic bodybuilding exercises. And, they are always interested in providing their readers with new ways to improve their workouts and bring about new muscle. So, when they decided they were going to start doing features of trainers, they contacted me to be the first. I’m so humbled that I was the very first name they thought of for this project.

MuscleMag filmed and photographed an extended training session I did with my friend and bodybuilder Fello Cambronero, who just won the OVERALL at the Sr. y Sra. musculo competition in Costa Rica. When it was all said and done, the editors liked the content so much they turned it into a BIG 7-page feature. I shared the excitment with Fello (Alex) Cambronero when the article was published because it was his first ever appreacnce in a major bodybuilding mag as a featured model. High five goes out to Alex and his lovely wife Maggy!

BJS: What’s your approach when working with bodybuilders? Specifically, do you use a mix of machines and free weights or do you prefer one versus the other. What about rep ranges?

NT: My approach with bodybuilders is to increase Hypertrophy, DUH! 🙂 That said, I still take a hybrid training approach with them. In that I incorporate mobility work, some 3D movements and even some athletic type drills into thier warm ups.

I absolutely use BOTH free weight and machines as they both have unique benefits the other doesn’t. Machines are actually a very consistent component in almost ALL of the bodybuilding workout programs I design because they allow for a constant tension on the muscles being worked, due to the Cam design of a machine. You don’t get that with free weights because they’re purely gravity dependant.

Just think about a Biceps curl with dumbbells; you get no resistance at the bottom (when your elbow is straight), and you don’t get much resistance at the top of the curl either because the lever arm is very short. Is that a bad thing?, NO! But, when doing biceps curls on machine, we can hit those angles gravity (i.e. free weights) wouldn’t allow.

This is why I don’t get caught up in these typical arguments over which is better, free weights or machines? We just do both because they both have benefits. And, we’ve found using them together get us results even faster because our workouts are more comprehensive.

For sets and reps: We use a variety of schemes. We’ll do basic 3-4 sets of 8-15 reps. We’ll do 4-6 sets of 4-6 reps. We love to alternate between those two basic rep schemes.

We’ll also use a wide variety of traditional and not so traditional overload concepts, such as: rest pauses, drop-sets, 21’s, 1.5 reps, etc. Along with many Performance U Hybrid Strength Training innovations such as 747s, Complexes, Triple Threat Protocols, 54321 workouts, etc.

BJS: Do you periodize bodybuilding routines or is it more intuitive?

NT: I always have some sort of plan. But, my “plans” are a moving target in that I’ll change something up a bit if needed.

One of my favorite, go-to bodybuilding program design strategies is to design a 6-week block program. In that 6-weeks your first (primary) exercise is alternated between two moves. The rest of the exercise in that workout stay the same for six weeks. But, the reps are undulated each workout. So, you have higher reps days, lower reps days, etc.

In short; We alternate and undulate! That’s my little saying, so I’ll know if anyone steals it 🙂

BJS: I know you have a new DVD on single leg training that was just released. What are the benefits of performing single limb exercise for the lower body?

![]()

NT: First, I’d like to say that just because I came out with a Single Leg Training DVD doesn’t mean I’m against double leg training. At Performance U, we use BOTH bilateral and unilateral lower-body training. This another situation where we don’t bother wasting our time arguing which is better because they both work!

When coaches and trainers stop being so concerned with being right over thier peers in these debates, and become more concerned with finding what right for thier clients in thier training, we’ll all be better off.

Anyway talk to most trainers about single leg training and they’ll likely show you pistol squats, single leg RDLs and Bulgarian split squats. Or, a small variations of those same basic movements. Those are great exercises, but they don’t even scratch the surface of what we’ve been able to do with our hybrid single leg training concepts and techniques. In other words, pistol squats, single leg RDLs and Bulgarian split squats are the checkers. But if you’re ready to play chess, get the Secrets of Single Leg DVD.

There are several benefits of single leg training that we’ve found:

Better balance: This one is obvious

Less Chance of Sports Injury – We hear lots about asymmetries and injury potential. But, the research I’ve seen says injury potential is more about strength asymmetries than anything else. In that, when you don’t control one side of your body as well as they other, you may be at a higher injury risk. Research shows us that you can still move a bit differently on each side (i.e. have a movement asymmetry), just as long as you can control the movement you can create on either side.

Better Body Control and Strength – By following the SAID principle (i.e. Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands), if you want to make sure you’re strong and able to control each side of your body, you train each side of your body independently to ensure BOTH side can do what they need to.

Improved Muscle Symmetry – Not only will have better strength/control on both sides potentially help you minimize injury. It can help you look better and build a more symmetrical looking lower-body.

Improved Sports Performance – Sports require stops, starts, direction changes and raising and lowering your center of mass. And, most of the time these action are done from a split, unilateral type stance where one leg is positioned to do more work than the other. We’ve found Single leg training can help ensure that both legs can get the job done, regardless of the position you’re in!

Less risk of hurting yourself in the gym – A high percentage of humans have a leg length asymmetry, which would make double leg training more risky because your body is having to deal with torque (from the leg length issue) along with the compression from the load you’re lifting when squatting or deadlifting. Single leg work allows us to not worry as much about this issue potentially hurting our clients and athletes. Plus, it gives us more capacity to use heavy double leg training when we feel it appropriate.

BJS: If you could pick one single leg exercise that provides maximal benefits for muscle development, what would it be?

NT: When speaking purely about muscle development (for bodybuilding) purposes, I’d say the knee tap squat. It’s basically a single leg version of a front squat, with a bit more hip hinge to bring in more glutes and hams. It’s the exercise pictured in the middle images of the back of the DVD cover (see the image to the left).

BJS: You state that the pistol squat might not be a good exercise. Why?

NT: Here’s what I wrote for Laree Draper about this, which she posted here;

Although the pistol squat is a trendy, cool looking and old-time exercise, it’s not something we use with our clients and athletes at Performance U.

We don’t feel the pistol squat exercise is “bad”, nor do we feel it’s dangerous. And, we don’t get caught up arguing against Pistols, or will we try to convince anyone to stop doing them. All we can do is share the training methodologies that make the most sense to us, along with the exercise applications we’ve found to work best for us.

That said, in our training with individuals of all levels from pro athletes to active seniors, we haven’t found the body positions and force production patterns involved in the pistol squat exercise to have as much value and functional carryover as some of the other creative, hybrid single leg squat variations we use, which I’ve displayed in the Secrets of Single Leg Training 2-DVD set.

You can see more about why we don’t use the pistol squat in this video

embedded by Embedded Video

Sure the pistol squat can make you stronger! It’s also very challenging exercise. And, if you enjoy doing them, then great! But, we’ve found other single leg squat training options, which we’ve found to be more beneficial because they more accurately match the body postures we see in sports and daily living; and they more closely replicate the force production patterns we are looking to improve with the clients and athlete we train.

BJS: Many thanks for sharing your thoughts Nick!

You can check out Nick’s Blog at: NickTumminello.com

Here’s the link to check out Nick’s Secrets of Single Training DVD

March 6, 2012

Bret Contreras Interview

Today’s post is an interview I conducted with uber trainer Bret Contreras. If you’ve read this blog over the past couple of years, you’ll know that I hold Bret in highest regard; someone I’m proud to call a friend and colleague. Not only does Bret have a terrific grasp of the research, but he is able to harness this info and apply it in highly innovative ways that few can match. This is the essence of evidence-based practice and no one does it better. Pure and simple, he’s one of the preeminent fitness professionals in the world.

Bret has just come out with a terrific monthly research review that synthesizes the current research from a practical perspective. I ask him about this as well as a number of other fitness-related topics that I’m sure you’ll find of interest.

BJS: Tell us a little about your background in the fitness field.

I’ve been weight training and reading about fitness for 20 years now. Like most in the fitness industry, I started accumulating tons of workout partners in my teens. This gradually evolved into personal training on the side until finally moving to full time training and strength coaching. Eventually I opened up my own facility which I had for a couple of years and then I switched to full time writing and researching.

No matter how busy I am, I always make sure to keep a few personal training clients so I don’t become too theoretical and esoteric like some researchers. Training real clients and having discussions with fellow strength coaches, trainers, and therapists keeps me grounded and humble.

BJS: You’re often referred to as “The Glute Guy.” How did you come to get this nickname?

To make a long story short, I was talking to legendary strength coach Martin Rooney a few years back at a Perform Better seminar and was discussing my EMG findings on the glutes. He jokingly mentioned that I give myself a name and threw out “The Glute Guy” as a suggestion. I liked the sound of it and went forth with the nickname, and now it has stuck. I’m very comfortable being known as The Glute Guy as I believe that the gluteus maximus is the most important muscle in sports since it’s heavily involved in running, jumping, cutting, and twisting – all extremely powerful movements. In my opinion it’s also the most important muscle for increasing women’s sex appeal.

BJS: What is your training philosophy?

I could write an entire essay on this, but it depends on the client and the goal.

For sport training, I believe that 80% of the potential gains from strength training come from “general” big lifts such as squats, deadlifts, bench press, bent over rows, military presses, and farmer’s walks. I believe that the big lifts can and should be modified to be more joint-friendly or replaced by biomechanically-similar exercises for lifters who don’t tolerate the big lifts very well. For example, front squats, hex bar deadlifts, incline presses, inverted rows, and neutral grip dumbbell military presses are suitable alternatives which are generally safer but will yield nearly identical adaptations.

I believe that the remaining 20% of potential gains from strength training come from exercises which are chosen by analyzing the specificity of the sport and position. The most underutilized principle of specificity is the direction of the forces in sport. Force vectors need to be mimicked in strength training to maximize the transfer of training. There are typical strength exercises that help bridge the gap between weight training and sport, such as hip thrusts, back extensions, Bulgarian split squats, cable hip flexion, cable woodchops, and JC band presses. Explosive lifts such as Olympic variations, jump squats, kettlebell swings, slideboard lateral slides, and medball throws; as well as towing exercises such as sled pushing bridge the gap as well. I believe that these special exercises put the finishing touches on a well-balanced general routine and significantly enhance the transfer of training.

For hypertrophy training, I believe in getting people really strong in a variety of exercises in a variety of rep ranges from a variety of angles while incorporating a variety of methods. How’s that for being vague? I’ll elaborate.

Let’s say I was aiming to achieve maximal pectoral hypertrophy for an experienced male client. In this case I would seek progressive overload in barbell and dumbbell bench and incline press variations for low to medium reps. I would incorporate targeted movements such as flat and incline fly and crossover variations for medium to high reps. From time to time I’d throw in weighted dips and push-ups (assuming they were well-tolerated by the client) for medium reps. I’d rely on traditional methods such as straight sets and pyramiding, in addition to utilizing neural overloading techniques such as the rest-pause method and pumping techniques such as the constant tension method with short rest times in between sets.

BJS: Do you believe in periodizing programs?

Of course I do, but not in the same manner as most coaches. There’s an Olympic Weightlifting coach out of Las Vegas named John Broz who sticks to six exercises year in and year out. His athletes are far more explosive than 99% of those who train with other coaches. They get really good at squatting and front squatting, cleaning and snatching, and power cleaning and power snatching, and their routines don’t vary from week to week and year to year. There’s something to be said for sticking to the basics and keeping it simple for strength and power gains, and Broz clearly demonstrates that fancy periodization is not a requirement for impressive training results.

However, it’s of utmost importance to keep clients and athletes injury-free. For this reason, I wouldn’t feel comfortable sticking with Broz’s approach, though I recognize its efficacy in terms of performance gains.

Currently I don’t train many clients but I’ll discuss some things that have worked well for me in the past as well as over the past year with some of the clients I’ve trained. First, I periodize according to skill level. I’ve learned much from Gray Cook over the years and think it’s imperative to focus on developing sound fundamental movement patterns which requires ideal levels of mobility, stability, and motor control. All clients and athletes need good squatting, hinging, and bridging patterns, as well as single leg and lumbopelvic stability. Corrective exercises should be utilized up front where necessary to fast-forward progress.

Once good technical form is reached on the big lifts, correctives are placed on the back-burner by moving them into the general warm-up, and the primary focus shifts to progressive overload. Getting stronger at the big lifts through a full range of motion without compromising perfect technical form is the name of the game. Once sufficient strength is reached following many years of strength training, main exercises should be rotated frequently and explosive repetitions via the dynamic effort method become more important.

Second, I sometimes periodize by targeting the weakest range of motion along the strength curve. For example, lifters who seem to fail down low and display disproportionately low flexed-range hip extension strength would be prescribed full squats, deficit reverse lunges, good mornings, and deficit deadlifts, which are all very hard in a deep position of hip flexion. Conversely, lifters who seem to fail at lockout and display disproportionately low end-range hip extension strength would be prescribed high box squats, rack pulls, back extensions, and hip thrusts, which target mid or end-range hip extension strength. I usually prefer to blend these movements together during programming but I’ve achieved great results with several clients by using this methodology. In fact several months ago I put 35 kgs (around 77 lbs) on a guy’s deadlift with this approach in just four weeks.

Third, from time to time I periodize by alternating clients between higher frequency approaches, higher volume approaches, and higher intensity approaches. Though this is a very common approach to periodization, I do it differently than many coaches as I switch things up more drastically than just tinkering with sets and reps – I’ll vary the exercises, manner of execution, and special methods as well. For example, during the high frequency phase I’d keep things simple and stick to the basics. During the high volume phase I’d employ bodybuilding techniques such as drop sets. And during the high intensity phase I’d employ HIT techniques such as breathing squats.

Fourth, I periodize by choosing new goals each month for my clients based on their input. One month we might try to set a record on maximal deadlifts. Let’s say a male client can deadlift 365 lbs, I may design the program around trying to get him to reach 405 lbs by the end of the month. Perhaps the individual wants to lose 5 lbs of fat for the month; I might add in 10-15 minutes of HIIT or MRT at the end of the session.

Fifth, I often periodize by utilizing an undulating (non-linear) approach, for example during a high frequency phase I might go with heavy weight for low reps on Monday, light weight for high reps on Tuesday, moderate weight for explosive reps on Thursday, and moderate weight for medium reps on Friday.

So there are a few ways in which I periodize programs. One approach to periodization that I don’t like is the classic (linear) approach that has you tapering down on rep ranges over time. I don’t like this method as individuals seem to get really good at whatever rep range they’re training at the expense of losing strength in the other rep ranges. For this reason I believe that every week should include some heavy low rep work, moderate medium rep work, and light high rep work for maximal efficacy. I do have some colleagues who have achieved good results using this approach so I recognize that it seems to work well for certain folks.

I should also mention that I am a big fan of programming according to instinct/gut feeling, though I don’t feel that this is a true form of periodization. Whether you call it auto-regulation, Cybernetic periodization, instinctive training, or biofeedback training, it’s all similar. You have a clear agenda and specific goal in mind for when your client enters the weight-room, but you tinker with the program on the fly based on verbal and non-verbal feedback from the client. I believe that all good programs rely heavily upon auto-regulation as it’s impossible to predict the precise psychological and physiological disposition of the client on a regular basis as there are just too many factors at play.

BJS: I know you’ve worked a lot with EMG. Do you consider it a useful instrument for studying biomechanics?

Hell yeah I do! Anyone who says otherwise hasn’t worked with EMG and doesn’t regularly read research. Strength & Conditioning writers are great at coming up with new ideas and new theories – in fact they’re the best. Sometimes these theories end up being right, but often the theories are either incorrect or incomplete. Researchers and sports scientists use various tools to learn more about the neuromuscular system and test hypotheses, and EMG is just one of these tools.

EMG is great because it measures the electrical activity in muscles; a measurement of the nervous system’s intent to fire the muscles. This gives us a reasonable measurement of muscle force (especially during isometric contractions and when non-fatigued) which is related to mechanical tension and ultimately, hypertrophy.

Like any tool, EMG has some shortcomings, but many of the shortcomings can be ameliorated, for example you can use multiple channels of EMG (i.e. using multiple electrodes on a particular muscle) during testing to cover more surface area and test more regions of the muscle. I like that EMG can be lined up with motion capture to analyze EMG timing relative to motion. EMG can be incorporated into muscle modeling along with force plate data and inverse dynamics to help predict joint torques, spinal loading, and muscle forces. Spinal biomechanist Stu McGill utilizes this approach in his experiments.

I learned so much valuable information when I conducted my extensive EMG experiments. I’d hook up 4 electrodes to various regions of muscles and perform tons of different exercises to see which movements activated the various muscles and regions of muscles best. Many times the experiments validated what I already knew through practical experience, but a few times I was very surprised at the results. However, after pondering the results and analyzing the biomechanics of the movements, the EMG findings made perfect sense.

My favorite aspect about EMG is that it’s the only tool that I know of that gives us numerical data to give us some idea as to muscle force. MRI and ultrasound are nice but they don’t provide numbers. Until we have a more practical way to measure actual muscle force, to me standardizing EMG to MVC is the way to go.

Many of my researcher colleagues and strength coach colleagues are quick to dismiss EMG because of various reasons and I always listen to their rationale. But usually I think their rationale is overly-critical and unfair. There are indeed limitations, but it’s the best tool we’ve currently got for seeing which exercises work a particular muscle or muscle part the best. Sure we can utilize other methods, such as MRI (there’s even a newer MRI technique called “STIR” which examines muscle damage following a workout), ultrasound, biomechanical analysis, “feeling the burn” during exercise, palpation, and simply doing a bunch of sets and seeing where you’re sore the next day, but EMG gives us actual numbers to use for comparison.

Bodybuilders have long claimed that you can perform specific movements to target a particular area of a muscle. Sports scientists were skeptical, but EMG has provided much evidence for their claims. Bodybuilders were right about the delts, traps, pecs, lats, abs, glutes, quads, hams, and calves; muscles don’t get worked uniformly across the various fibers and specific exercises can be used to strengthen or hypertrophy a particular region. This is useful for functional purposes and sport, for bodybuilding purposes, and for rehabilitation purposes. We’re now learning that the nervous system is skilled at determining which parts of the muscles have the best leverage at a particular range of motion and it fires those regions when appropriate to produce efficient movement – this has been coined “functional differentiation.”

Just recently EMG was used to dispel the “corset hypothesis” that most physical therapists and strength coaches subscribe to; we learned that the transverse abdominis doesn’t contract uniformly during unilateral limb movement. There are many excellent uses for EMG and when used by a skilled practitioner who understands its strength and limitations, it’s incredibly valuable.

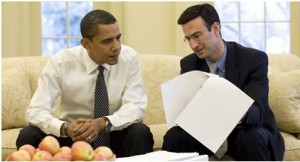

BJS: You have a new product out that I know you’re quite excited about. Tell us about it.

I sure do. It’s a research review service that I started with my colleague Chris Beardsley – someone who I respect immensely. Beginner coaches and lifters need to spend time in the trenches gaining experience under the bar and working with other people. They don’t have time to sift through the research, and even if they did have the time, chances are they don’t have access to the journals.

Yet every young and advanced athlete, lifter, trainer, therapist, and coach could benefit considerably by receiving a monthly report that summarizes the latest findings in strength & conditioning, biomechanics, physiology, and physical therapy. This is exactly what Chris and I will do each month; we’ll pick out the 40-50 best articles for the month with a good blend from each category and summarize and email them to you in a nice PDF format.

Think about it – the President of the United States has advisers that hand him reports so he can stay informed. I’d like for you to feel like the President each month, so let Chris and me do the hard work for you so you can stay abreast of the literature and have an edge on your competition without taking up too much of your precious time.

For just $10/month you can be in the know by subscribing at www.StrengthandConditioningResearch.com. I can’t begin to tell you how much more intelligent and informed I am as a coach following a year of intensive studying and researching. It is my hope that strength & conditioning enthusiasts will take my word for it and subscribe as I can’t imagine anyone regretting it – so far all the feedback I’ve received has been very positive. Thanks for the interview Brad – I appreciate the opportunity!

Check out Bret’s blog at: Bretcontreras.com

Check out Bret’s review publication at: StrengthandConditioningResearch.com

August 23, 2011

Crunches, the NY Times, and Open Access to the NSCA Journal Article

I was recently interviewed by the New York Times about the review article that I co-wrote with Bret Contreras titled, “To Crunch or Not to Crunch.” The Times article explored the topic as to whether crunches were worth the effort. My quotes were somewhat misconstrued here.

To set the record straight, I stated that it is generally superfluous to perform hundreds of crunches in a training session. The reason? Doing so has little applicability to every day life. After all, when do you repeatedly flex at the spine hundreds of times? As a general rule, core endurance is most needed in static postures and this is best achieved through isometric exercise, not flexion movements.

On the other hand, I pointed out that dynamic core strength can be important for carrying out many sporting movements and activities of daily living (as well as to optimize the “six pack” appearance that many people covet). To develop dynamic strength and muscle development, you need to perform low-to-moderate repetitions (within a range of about 6-15 reps). In the times piece, it came across as if I was advocating just a single set of crunches. This isn’t the case. Several sets are required to achieve optimal results.

Moreover, the sets must be challenging. If you can easily perform the target rep range, you need to add resistance! This can be achieved by either holding a weight (i.e. dumbbell, weighted plate, medicine ball,etc) during a crunch, or by performing spinal flexion on a cable apparatus (e.g. kneeling cable crunch).

On a side note, I’m happy to report that the NSCA has made the review article that Bret and I wrote free to read. Generally you must be a member of the NSCA to get access to articles appearing in the Strength and Conditioning Journal. However, because the article has received so much attention, the powers that be have provided open-access to all. Give it a read at the link below and let me know your thoughts.

Stay Fit!

Brad

October 9, 2023

Does supervision during resistance training enhance increases in muscle strength and size

Does supervision during resistance training enhance increases in muscle strength and size in trained lifters compared to unsupervised training?

That’s the question our lab recently set out to answer. The study, led by my master’s student Max Coleman, has now been published in the Journal of Sports Sciences and the results have wide-ranging practical implications.

If you want to delve into the fine points of the methods and findings, give the paper a read. For those who’d prefer a consumer-friendly synopsis, here’s the scoop…

What We Did

We randomized 45 young, resistance-trained men and women to perform a total-body resistance training program either in a supervised (SUP) or unsupervised (UNSUP) manner across an 8-week study period. Both groups performed the exact same exercises (front lat pulldown, machine shoulder press, machine chest press, cable triceps pushdown, dumbbell biceps curl, plate-loaded leg press, machine leg extension and machine leg curl) and program variables (3 sets of 8-12 RM for each exercise with 2 minutes rest between sets).

Participants in SUP were directly supervised throughout each rep of every session, with researchers verbally encouraging them to carry out all sets to volitional failure (i.e., the point where an individual felt that he/she could no longer complete an additional repetition) and adjusting exercise technique when appropriate. Alternatively, those in UNSUP were taken through an acclimation session to demonstrate proper technique on the given exercises and instructed to carry out all sets to volitional failure throughout the training program; they charted their workouts and emailed the corresponding logs to the research staff on a weekly basis.

We assessed the following measures before and after the training program: (1) body composition via bioelectrical impedance analysis; (2) muscle thickness of the biceps, triceps, and quads via ultrasound; and, (3) maximal strength in the bench press and squat via 1 repetition maximum testing.

What We Found

In regard to hypertrophy, the SUP group showed greater increases in muscle thickness for the triceps brachii, the upper portion of the lateral thigh and all regions of the mid-quadriceps. Alternatively, the biceps brachii and mid- and lower aspects of the lateral thigh showed relatively similar hypertrophy between groups.

From a strength standpoint, the SUP group showed greater increases in the 1RM squat; increases in the 1RM bench were relatively similar between groups.

Of note, there were a considerably greater number of dropouts in UNSUP (n=7) compared to SUP (n=2) across the study period.

What Do the Results Mean?

Overall, the findings indicate that direct supervision has a beneficial effect on strength and hypertrophy in recreationally trained young men and women. The magnitude of the effects ranged from relatively small to quite large, suggesting that adaptations could be practically meaningful.

Although we did not attempt to explore the underlying mechanisms for results, it can be hypothesized that intensity of effort was a contributing factor. There is compelling evidence that training with a high level of effort is necessary to optimize muscular gains. Not only did our research team verbally coach participants to go to failure on each set, but findings also may have been influenced by the fact that people try to do their best when being observed (the so-called “Hawthorne Effect”). Notably, when asked about their perceived effort at the end of the study, almost all participants said they trained harder than they ever had before. This would suggest that those in the UNSUP group were generally training with less effort, perhaps below the threshold required for max gainz.

Results also may have been partially attributed to improved training technique. Although the participants all had been training consistently for at least one year, some did not perform exercises in a biomechanically efficient manner and/or did not properly control the weights throughout each repetition (especially on the eccentric action). For those in the SUP group, our research team corrected technique during a set when appropriate, helping to ensure that muscles were optimally stimulated. We can only speculate on the matter, but it’s reasonable to assume that a number of participants in the UNSUP group likely trained with substandard technique, potentially diminishing results.

Another important finding was that the UNSUP group had far more dropouts than the SUP group. At the end of the study, several participants in SUP stated that the supervision made them feel “accountable” to show up for the training sessions. Considering that exercise adherence is paramount to achieving results, supervision would thus be beneficial to a substantial portion of the general population who are not sufficiently motivated to train consistently.

Take-Home Conclusions

So what are the practical implications of these findings?

On a general level, direct supervision during resistance training appears to enhance muscular adaptations for a majority of the recreationally trained lifting public. The supervision could be in the form of a qualified personal trainer or attentive workout partner; essentially, someone who monitors exercise technique and suggests corrections where appropriate and motivates the lifter to push sufficiently hard during each set. Given that individuals who are relatively new to resistance training generally have spotty technique and perhaps a poor understanding/motivation to progressively challenge their muscles, they may benefit to an even greater extent from a supervised program. Alternatively, some advanced lifters (i.e., bodybuilders, etc) may be internally motivated to consistently train with high intensities of effort and hence may not meaningfully benefit from supervision.

The results also suggest that research studies intending to investigate the efficacy of resistance training-induced strength/hypertrophy outcomes should carry out data collection in a supervised environment; it’s the only way to ensure that participants train in a manner consistent with optimizing results. However, while this approach may enhance research efficacy, there may be a disconnect when generalizing the findings from resistance training research carried out under supervision to the recreational lifting public. Namely, if most lifters train suboptimally on their own, they cannot necessarily expect to achieve results similar to those found under supervised conditions. The tradeoff needs be considered by researchers when designing resistance training interventions as well by practitioners when interpreting study findings for program prescription.

September 25, 2022

Should You Reduce Volume During a Cut? Results from Our Original Research

Evidence indicates a dose-response relationship between resistance training volume and muscle hypertrophy, with higher volumes (up to a certain point) leading to greater growth responses. However, this evidence is specific to a program intended for optimal muscle-building; when cutting, it is often advised to reduce training volume to facilitate recovery and thus sustain performance over time (and perhaps avoid overtraining).

While dogma on the topic has been generally accepted in bodybuilding circles, the theory is based primarily on logical reasoning (and in some cases, overextrapolation of research that did not involve an energy deficit). Accordingly, our group previously decided to delve into the literature and carry out a systematic review to draw more objective conclusions. Contrary to popular claims, our extensive review of literature found no compelling evidence of a benefit to decreasing resistance training volume during a cut phase, and some evidence even seemed to suggest a potential detriment to volume reduction for sparing lean mass (see my write up on the paper here). While this raises cause for skepticism, the findings were based solely on correlational evidence, which limited the ability to draw causal inferences; no study had directly compared the effects of higher versus lower volumes during a controlled energy deficit.

Until now…

We followed up the review by conducting an original study that endeavored to directly examine how resistance training volume affects body composition during a cutting phase. The study, titled “Resistance Training Volume Does Not Influence Lean Mass Preservation during Energy Restriction in Trained Males”, was recently published in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports.

For those who want the consumer-friendly version, here’s the scoop…

What We Did

We assigned 38 young, resistance-trained men to initially perform a one-week moderate volume deload phase arranged in an upper-lower body split routine format. Training consisted of 3 sets per exercise for large muscle groups and 1 set per exercise for the arms and calves; each body region was trained twice per week with a target loading zone of 10 reps per set.

We then randomized the participants to either continue training with the deload routine or to perform a higher volume protocol (5 sets per exercise with 3 sets per exercise for arms) over a 6-week mesocycle. For the quadriceps, volume amounted to 20 sets per week for the higher volume group and 12 sets per week for the moderate volume group.

During the deload phase, we instructed participants to consume a weight maintenance diet (45 kcal/kg/day). For the intervention period, we prescribed a hypocaloric diet (30 kcal/kg/day) so that participants would achieve an energy deficit for the purposes of weight loss. Protein intake was set at 2.8 g/kg/day fat-free mass with consumption of the remaining calories from carbohydrate and fat left to individual preference. Participants provided daily self-reported nutritional info via an online app, allowing us to track dietary compliance.

We assessed muscle thickness of the rectus femoris at two sites (50% and 75% of femur length) via B-mode ultrasound and body composition via multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis. In addition, we assessed subjective measures of sleep duration, sleep quality, and state of mood using questionnaires.

What We Found

Both groups lost an average of 1.7 kg (~4 pounds) during the 6-week hypocaloric diet, with lean mass accounting for ~30% of these losses in the higher volume group and ~52% in the moderate volume group. Muscle thickness measures of the rectus femoris essentially did not change across the study period for either the higher or moderate volume condition. Subjective measures of participants’ sleep duration and quality did not change throughout the study period, nor did their state of mood.

What are the Practical Implications of Findings

The results of our study indicate that resistance training volume has neither a beneficial nor detrimental effect on muscle development during a cutting phase. The body composition data showed a slight loss of lean mass for both groups despite a relatively high protein intake (~2.8 g/kg/day of fat-free mass). However, the amount of these losses were within the margin of error of the measurement, and thus likely of little practical meaningfulness. Indeed, direct site-specific measures of muscle growth did not show appreciable changes for either condition. On the surface, the results seem to suggest that you need to be at least at caloric maintenance (or perhaps in a surplus) to take advantage of higher training volumes from a muscle-building standpoint.

Intriguingly, subjective measures of sleep and mood were unaltered by training volume. Participants in both groups rated their sleep quality as “moderate” and neither group reported issues with sleep disturbance. Similarly, indices of mood were generally unchanged over the course of the intervention, irrespective of group allocation. When taken as a whole, these results indicate that relatively high training volumes are well-tolerated during periods of energy restriction and do not negatively affect performance, at least over a relatively short mesocycle. This seemingly refutes the claim that volume needs to be reduced while cutting.

While our study provides preliminary evidence as to the effects of training volume during a cut phase, there are still many questions left to be answered. These include:

***We only measured hypertrophy at two sites on the rectus femoris. What about other muscles? Perhaps the upper body may respond differently than the lower body? Or perhaps the other quad muscles may respond differently than the rectus femoris?

***Our sample was comprised exclusively of young men. What about other populations? Our previous review on the topic suggested that women seem to retain more lean mass with higher volumes compared to males. Perhaps aging may have a modifying effect as well. Evidence indicates that older individuals require more recovery, which in turn may warrant alterations in training volume.

***Our protocol involved a relatively high vs relatively moderate volume program. What about programs with higher or lower volume protocols? Would more extreme volume variations perhaps produce different results?

***We employed a relatively modest caloric deficit, with subjects losing ~3/4 pound of weight per week. What about a larger deficit? It is not uncommon for people to target 1 to 2 pounds of weight loss per week during a cut phase, but it’s unclear if/how volume may affect such practices.

***Participants in our study were relatively lean (baseline body fat percentage in the high teens). What about lower body fat levels? Previous research from our lab (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33105363/) indicates that losses in lean mass rise exponentially when body fat dips below ~10%. Could volume have an impact on these losses, either positive or negative?

All of these limitations cloud our ability to draw strong inferences on the topic and thus warrant further investigation.

Take-Home Conclusions:

Our findings provide preliminary evidence that resistance training volume does not influence body composition changes during a relatively brief (6 week) cut phase. The results suggest that volume can be reduced during such a phase without having a detrimental effect on lean mass. Alternatively, there are no benefits to decreasing volume (other than better time-efficiency), as the lower volume protocol did not improve results or enhance subjective measures of sleep and mood. Importantly, we need to be cautious in drawing strong conclusions on the topic. Given the limitations of the study, this should be considered an initial piece in the puzzle that requires follow-up studies to fill in the gaps in our knowledge. Stay tuned…

September 11, 2022

Does Intense Stretching Between Sets Increase Muscle Growth?

The bodybuilding community is forever seeking to develop advanced training methods that enhance muscle growth. Loaded stretch has long-been proposed as a potential strategy to increase gains. My close friend and colleague, the late, great John Meadows, was a huge proponent of including loaded stretch as a component in bodybuilding program design. Commonly, but not always, this practice is incorporated into the inter-set rest period between sets of an exercise.

Research in animals has consistently shown a benefit to loaded stretch protocols. However, there have only been a few human studies to date that attempted to investigate the topic in a controlled fashion. Thus, our lab decided to conduct a study to determine if loaded stretch performed between sets in a resistance training routine influences muscular adaptations in the calf muscles. The study, Loaded inter-set stretch may selectively enhance muscular adaptations of the plantar flexors, was recently published in PLoS One (and is open-access so that all are able to read for free).

For those who want the consumer-friendly version, here’s the scoop….

What We Did

The study was led by my master’s degree student, Derrick Van Every, with support from our terrific team of research assistants. To reduce potential confounding from genetic and lifestyle factors, we employed a within-subject design where all participants performed both conditions during the same session in counterbalanced fashion. As such, we randomized the legs of young, untrained men to perform 4 sets of straight- and bent-knee calf raises with 2 minutes rest between sets. One of the participants’ legs rested passively during the rest period (consistent with traditional training protocols) while the other leg descended into a loaded stretch (i.e., dorsiflexion) immediately after the end of the set. The stretch condition was held for 20 seconds and then participants rested passively for the remaining duration of the rest interval. Each set targeted 8-12 sets carried out to volitional failure. The training component of the study lasted 8 weeks.

To determine if the strategy influenced hypertrophy, we assessed pre- to post-study changes in muscle thickness of the calf muscles (lateral and medial gastrocnemius, as well as the soleus). We also measured changes in isometric strength with the knees straight and bent.

What We Found

Soleus hypertrophy was modestly greater for the loaded stretch condition. The magnitude of effects ranged from negligible to relatively substantial compared to passive rest (~9% greater). The lateral gastroc showed a slightly advantageous effect for loaded stretch, but the range of values were of questionable practical meaningfulness. The medial gastroc showed neither a benefit nor detriment to loaded stretch.

Somewhat surprisingly (at least to me), strength was modestly enhanced by loaded stretch. The effects ranged from negligible to potentially meaningful (?10% of the baseline strength).

What are the Practical Implications of Findings

Our study suggests that adding brief (20 seconds) loaded inter-set stretch bouts to a resistance training program may in fact promote modest improvements in muscle growth, perhaps specific to certain muscles more than others. In addition, there may be modest improvements in muscle strength as well. Interestingly, the beneficial effects occurred despite a decrease in volume load (sets x reps x load) of ~5 to 12%.

Previous research shows conflicting results on the value of intense inter-set stretch, with some studies indicating a hypertrophic benefit and others not. Although it’s difficult to speculate on the reason(s) for these discrepancies, it’s interesting to note that our study found that beneficial effects were greatest in the soleus muscle. The soleus is a slow-twitch dominant muscle, comprised of ~80% type I fibers. It’s possible that type I fibers may be more anabolically responsive to the higher time-under-tension compared to type II fibers. It also is possible that these fibers may have additional inherent properties predisposed to loaded stretch following performance of eccentric actions (e.g., differences in muscle architecture). Of note, research in animal models also tends to show greater gains in slow-twitch dominant muscles. Alternatively, the results may simply be a chance finding that occurred irrespective of fiber type composition. Replication is needed to provide more insight on the topic.

A limitation of the study is that participants were untrained men. This population was chosen so that we could isolate training only the calves without confounding from other multi-joint leg training (e.g., compound lower body exercises involve plantarflexion); it would have been near impossible to recruit trained subjects willing to give up training their thighs for a couple of months. Thus, it remains to be determined if similar results are achieved in trained individuals as well as in women. In addition, the findings are specific to the calf muscles; we cannot necessarily extrapolate similar results in other muscles of the body. Each study is but a piece in the puzzle of theory development, so further research is needed to better understand the nuances of the topic.

Take-Home Conclusions

From a practical standpoint, loaded stretch performed between sets may be a viable strategy to increase muscular development. Based on our findings, the improvements are relatively modest and their practical meaningfulness would depend on your ultimate goals (e.g., more relevant to those interested in bodybuilding vs general fitness). Although speculative, benefits may be best achieved when the stretch is performed immediately after the final eccentric action to take advantage of the associated passive force enhancement effects on the muscle .

I’d note that the strategy employed in our study did not increase the duration of the workout, making it a time efficient option. Given that there does not seem to be a downside to inclusion of loaded inter-set stretch, it’s a strategy worth experimenting with if your goal is to maximize gains.

August 20, 2017

Warming Up Prior to Resistance Training: An Excerpt from “Strong & Sculpted”

Below is an excerpt from my book, Strong & Sculpted that discusses my current approach to warming up prior to resistance training. I neglected to include a chapter on the topic in my book, M.A.X. Muscle Plan so for those following this program, the same info applies.

Warm-Up

To prepare your body for the demands of intense exercise, you should warm up prior to your lifting session. The warm-up contains two basic components: a general warm-up and a specific warm-up. Here’s what you need to know about each component for a safe, effective workout.

General Warm-Up

The general warm-up is a brief bout of low-intensity, large muscle–group, aerobic-type exercise. The objective is to elevate your core temperature and increase blood flow, which in turn enhances the speed of nerve impulses, increases nutrient delivery to working muscles and the removal of waste by-products, and facilitates oxygen release from hemoglobin and myoglobin.

A direct correlation exists between muscle temperature and exercise performance: when a muscle is warm, it can achieve a better contraction. As a rule, the higher a muscle’s temperature is (within a safe physiological range), the better its contractility. And because better contractility translates into greater force production, you’ll ultimately achieve better muscular development.

What’s more, an elevated core temperature diminishes a joint’s resistance to flow (viscosity). This is accomplished via the uptake of synovial fluid, which is secreted from the synovial membrane to lubricate the joint. The net effect is an increase in range of motion and improved joint-related resiliency. Better yet, these factors combine to reduce the risk of a training-related injury.

Suffice it to say that the general warm-up is an important part of a workout.

Virtually any cardiorespiratory activity can be used for the general warm-up. Exercises on equipment such as stationary bikes, stair climbers, and treadmills are fine choices, as are most calisthenic-type exercises (e.g., jumping jacks, burpees). Choose whatever activity you desire as long as the basic objective is met.

The intensity for the general warm-up should be low. To estimate intensity of training, I like to use a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale. My preference is the category-ratio RPE scale, which grades perceived effort on a scale from 0 to 10 (0 is lying on your couch, and 10 is an all-out sprint). Aim for an RPE of around 5, which for most people is a moderate walk or slow jog. You can use the talk test as an intensity gauge. With this method, you base intensity on your ability to carry on a conversation; if you have to pause to take a breath while speaking a sentence, you’re working too hard.

Five to ten minutes is all you need for the general warm-up—just enough to break a light sweat. Your resources should not be taxed, nor should you feel tired or out of breath either during or after performance. If so, cut back on the intensity. Remember, the goal here is merely to warm your body tissues and accelerate blood flow—not to achieve cardiorespiratory benefits or reduce body fat.

Specific Warm-Up

The specific warm-up can be considered an extension of the general warm-up. By using exercises that are similar to the activities in the workout, the specific warm-up enhances neuromuscular efficiency for the exercise you are about to perform. In essence, your body gets to rehearse the movements before you perform them at a high level of intensity, translating into better performance during your working sets.

To optimize transfer of training, the exercises in the specific warm-up should mimic the movements in the workout as closely as possible. For example, if you are going to perform a bench press, the specific warm-up would ideally include light sets of bench presses. A viable alternative would be to perform push-ups because the movement pattern is similar to that of a bench press, although the specificity, and thus transfer, would not be as great as with light sets of the given movement. Always stop specific warm-up sets well short of fatigue. The object is not to fatigue your muscles, but rather to get a feel for the exercise so that you’re physically and mentally prepared for intense training.

The specific warm-up is particularly important when training in low-repetition ranges (~ five reps or fewer). I recommend at least a couple of specific warm-up sets per exercise during low-rep training. As a general rule, the first set should be performed at ~40 to 50 percent of 1RM; and the second set, at ~60 to 70 percent of 1RM. Six to eight reps is all you need in these sets—any more is superfluous and potentially counterproductive. Following the specific warm-up, you should be ready and able to plow into your working sets.

The need for specific warm-up sets in medium- to high-rep-range training remains questionable. I recently collaborated on a study that investigated the effects of a warm-up on the ability to carry out repetitions to failure at 80 percent of 1RM (a weight that allows performance of about eight reps) in the squat, bench press, and arm curl (Ribeiro et al., 2014). The verdict: Warming up showed no beneficial effects on the number of repetitions performed in medium- to high-rep-range training nor in a measure called the fatigue index, which is a formula that assesses the decline in the number of repetitions across the first and last sets of each exercise.

At face value these results suggest that warming up is pretty much useless prior to submaximal resistance training. Despite the currently held belief that a specific warm-up enhances exercise performance, no benefits were seen when compared to no warm-up at all. Intuitively, this seems to make sense given that the initial repetitions of a submaximal lifts are in effect their own specific warm-up, and increasing core temperature might be superfluous from a performance standpoint when multiple reps are performed.

It should be noted, however, that we found a slight advantage to performing a specific warm-up prior to the squat (although results did not rise to statistical significance); the specific warm-up prior to the biceps curl seemed to be somewhat detrimental. Thus, more complex movement patterns seem to benefit from the practice effect of a specific warm-up, although this would be of no value prior to simple exercises.

Taking the evidence into account, here’s my recommendation: When performing medium-rep-range work (8 to 12 reps per set), perform a specific warm-up prior to multijoint free weight exercises. One set at about 50 percent of 1RM is all you need to obtain any potential benefits.

Specific warm-up sets are not necessary when training with high reps (15+ reps per set). In this instance, because you’re already using light weights, the initial repetitions of each working set serve as rehearsal reps. What’s more, performance of warm-up sets is counterproductive to the goal of maximizing training density to bring about desired metabolic adaptations.

What About Stretching?

Static stretching is commonly included as part of a prelifting warm-up. This method of flexibility training involves moving a joint through its range of motion to the point where you feel slight discomfort, and then holding the position for a period of time (generally about 30 seconds). Most protocols involve performing several sets of static holds and then moving on to stretches for other muscles. It’s commonly believed that the addition of stretches to a warm-up further reduces injury risk while enhancing physical performance.