September 3, 2018

More on the dose response relationship between volume and hypertrophy

A number of people have asked about our recent paper Resistance Training Volume Enhances Muscle Hypertrophy, but Not Strength, in Trained Men, wondering if the hypertrophy results may be related to swelling (edema) from post-exercise muscle damage. Indeed, research shows that an acute bout of unaccustomed exercise can lead to swelling for several days, confounding ultrasound measures.

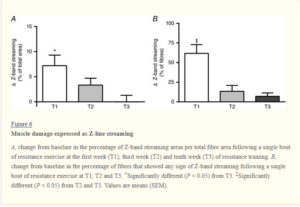

However, there is a well-established phenomenon called the repeated bout effect, whereby continual performance of the same routine markedly attenuates damage-related symptoms compared to the initial bout. In fact, there is evidence that just one additional bout of the same exercise protocol reduces the swelling response to only one-third of the initial bout. Consistent training with the same routine further diminishes these effects, as eloquently shown in a study by Damas et al who tracked indices of muscle damage across 10 weeks of regimented resistance training carried out to volitional muscular failure. As shown in the graph above, damage was substantial after the initial training session. By the fifth workout, damage was substantially reduced and by the 19th workout, damage was practically inconsequential as measured 48 hours post-exercise. Post-testing for our study was done 48 to 72 hours after the last bout of a routine that was performed 24 times over an 8-week period. Thus, while I can’t completely rule out the possibility that there was swelling in the muscles, it would seem highly unlikely that this would have confounded our findings. This is particularly true given that our subjects were resistance-trained men with 4+ years training experience, who were already acclimated to the stresses of regular lifting.

On a separate note, in the discussion section of our paper we briefly discussed the results of another study on the topic carried out by Ostrowski et al. We noted that, similar to our study, the results of Ostrowski et al supported the hypothesis that volume is a primary driver of hypertrophy. Some have asked why we did not discuss the dose-response implications between their study and ours. This was a matter of economy. Comparing and contrasting findings would have required fairly extensive discussion to properly cover nuances of the topic. Moreover, for thoroughness we then would have had to delve into the other dose-response paper by Radaelli et al, further increasing word count. Our discussion section was already quite lengthy, and we felt it was better to err on the side of brevity. However, it’s certainly a fair point and I will aim to address those studies now.

Ostrowski et al carried a study in resistance-trained men, who were randomized to perform either 1, 2 or 4 sets per exercise. For triceps, our results were somewhat inconsistent with theirs. Whereas we showed that muscle thickness increased by 1.1%, 3% and 5.5% for the low, middle and high volume groups, respectively, they showed increases of 2.3%, 4.7% and 4.8%, respectively. The primary difference between findings is that Ostrowski showed similar growth between middle and high volume groups while ours showed a graded increase from low to middle to high. The overall differences were modest on this outcome. Possible reasons for the discrepancy could be due to differences in methods. Ostrowski et al used a typical bodybuilding-type routine that involved a four day split. Subjects trained legs on Day 1; chest and shoulders on Day 2; back and calves on Day 3; and arms on Day 4. On the other hand, our study employed a total body routine where all muscles were trained in the same session, three times per week. Ostrowski et al also had subjects perform single joint exercises for the triceps in addition to their contribution in pushing movements, whereas subjects in our study just performed pushing movements. As discussed in the limitations of our paper, there is evidence that multijoint movements produce similar hypertrophy to single joint movements, but we cannot rule out that inclusion of targeted training for the triceps influenced differences in results. I’d note that the triceps data from our study was the least compelling of the four muscles measured for showing an effect of volume on hypertrophy. Thus, given the fairly low response across conditions, the discrepancy also could be due to the effects of random chance.

With respect to lower body hypertrophy, our results are somewhat in concert with those of Ostrowski et al. Ostrowski et al found quadriceps thickness increased of 6.8%, 5%, and 13.1% for low, middle and high volume groups, respectively. These findings are fairly consistent with ours, which found an increase in mid-thigh hypertrophy of 3.4%, 5.4, and 12.5%, and lateral thigh hypertrophy of 5.0%, 7.9, and 13.7% in the low, middle and high volume conditions, respectively. The fact that their low and middle volume conditions did not show differences may be related to the low volumes performed in both of these conditions (3 and 6 sets per muscle per week, respectively) whereas the high volume condition performed 12 sets per muscle per week. It’s also interesting that much greater levels of volume were required to achieve similar hypertrophic responses in the quadriceps between our study and that of Ostrowski; the reasons for this are not clear.

Our findings are consistent with those of Radaelli et al, who randomized young men to perform either 1, 3 or 5 sets per exercise per week. The subjects were military personnel who regularly performed calisthenic-type exercise but were not involved with resistance training at the time of the study. They reported increases in biceps thickness of 1.1%, 7.8% and 17% whereas our study found post-study increases in biceps thickness of 1.6%, 4.7% and 6.9% for the low, middle and high volume groups, respectively. For the triceps, Radaelli et al found pre- to post-study increases of 0%, 1.7%, and 20.8% for the low, middle and high volume groups, respectively. As noted above, we found 1.1%, 3% and 5.5% for the same conditions. Thus, both studies showed a dose-response relationship between volume and hypertrophy, albeit Radaelli et al reported much greater increases for the highest volume condition. Radaelli et al did not report results for lower body hypertrophy, so we cannot contrast findings in this regard. The reasons for similarities between findings potentially can be attributed to the fact that our designs were similar. Both studies employed graded doses of 1, 3 and 5 sets per exercise per session and both had subjects perform a total body routine, three days per week. A difference between studies is that subjects in Radaelli performed single joint exercises for the biceps and triceps whereas our study only performed multijoint movements for these muscles. Moreover, their study lasted 6 months whereas ours lasted 2 months.

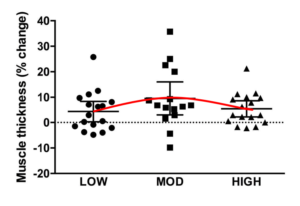

Since acceptance of our paper, two additional studies have been published on the topic. I’ll discuss the ultrasound results, as they are specific to our findings. Heaselgrave et al randomized resistance-trained men to perform either 9, 18 or 27 sets of biceps training each week. Subjects performed a combination of multi and single joint exercises for the muscle. Although results did not rise to a level of statistical significance, scrutinization of the individual data appears to show a fairly clear hormetic response (i.e. inverted U), with results peaking in the middle volume condition as shown in the graph above. This study had a couple of notable limitations. For one, subjects were allowed to train on their own outside of the study but were advised not to perform any direct biceps exercise. Although subjects did not report significant confounding from outside training, it is known that self-report can lack accuracy and it therefore remains questionable whether additional training was in fact carried out. Moreover, the subjects in the higher volume conditions trained two days per week while the lowest volume condition trained one day per week. Thus, this study in actuality had two treatment variables, confounding the ability to draw causality on volume alone.

Finally, Haun et al recently carried out a study in resistance-trained men. The study employed a somewhat unusual design, whereby volume was ramped up each week over the course of 6 weeks, beginning with 10 sets per muscle per week and progressing to 32 sets per muscle in week 6. Only 4 exercises were employed: back squat, bench press, stiff legged deadlift, and lat pulldown. A strong point of this study was that they employed midpoint testing after the 3rd week, thereby providing insights into how changes occurred over time. Muscle thickness for the biceps brachii increased from baseline to the midpoint, but then attenuated by the end of the study. This suggests results peaked at 20 sets per muscle per week. Alternatively, results for the vastus lateralis showed no significant changes from mid to post testing, but significantly increased from midpoint (20 sets/muscle/week) to the end of the study (32 sets/muscle/week). Interestingly, the authors also carried out biopsy testing and found that CSA of the vastus lateralis significantly decreased from baseline to mid but then significantly increased from mid to post. It should be noted that the overall magnitude of the increases in this study were quite modest. That may be due to the design, whereby subjects performed 10 reps at 60% of 1RM each set. This is a relatively light load for trained subjects, and it can be speculated they weren’t sufficiently challenged. Another factor to consider is that volume was progressively increased each week, so subjects only trained at a given volume for 1 week. It is therefore difficult to extrapolate the effects of training at a prescribed volume over multiple weeks.

In summing up the literature to date, the one thing that appears clear is that volume plays a fairly prominent role in maximizing growth, but nevertheless significant hypertrophy can be obtained at fairly low volumes. It’s difficult to reconcile discrepancies between studies given differences in methodology. And as as is almost always the case in an applied science such as exercise, prescription will be specific to the individual as there are large interindividual variances associated with response to volume. The astute fitness pro will take the current research into account and then use his/her expertise to customize program prescription, taking into account the potential benefit balanced against the time commitment involved.

4 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)

Thank you for this great information.

It’s not meant to demean your great research at all, but I always wonder when I see study after study after study with exclusively male subjects; Why are there never studies with female subjects?

Comment by Melissa — September 3, 2018 @ 8:20 pm

[…] Brad Schoenfeld has also addressed the edema issue, pointing out that the repeated bout effect would minimize or eliminate changes in edema. I've seen some people link to this study showing muscle swelling in trained subjects after 9 sets of leg press and squats to failure. While the subjects in that study had experience with squat and leg press, they typically only trained legs once per week, which would limit the repeated bout effect, and make swelling more likely from such a session. […]

Pingback by Responding to Critiques of Our Volume Study – Weightology — September 3, 2018 @ 8:38 pm

Dear Dr. Schoenfeld,

I’m a big fan of your work, and I’ve read this post and the original paper with interest.

In that study, I noticed body weight was measured. It seems it was measured pre, but not post-intervention. Can I ask if this is correct?

What I was actually wondering here was if there might have been differences in body weight by group pre or post-intervention. This is not presented in the paper; has your team by any chance carried out these analyses in unpublished fashion?

Thanks for reading this far!

Respectfully,

Carl Juneau, PhD

Comment by Carl Juneau, PhD — September 24, 2018 @ 5:18 am

[…] to the first post, which addressed at least some of the questions that he had raised. Lyle also failed to link to this blog post by Brad Schoenfeld which also addressed some of the questions. So already Lyle is not giving a full presentation of […]

Pingback by Lessons in Confirmation Bias, Double Standards, Strawmen, Edema, Blinding, and Research Critiques: My Final Response on our Volume Study – Weightology — September 24, 2018 @ 5:39 pm