May 3, 2012

Stiff-Legged Deadlift Performance: Facts and Fallacies

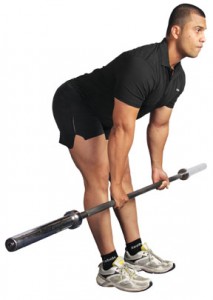

The stiff-legged deadlift (a.k.a. straight-legged deadlift) is one of the most popular resistance exercises for developing the glutes and hamstrings. Unfortunately, it’s also one of the most misunderstood. Many lifters have misguided notions about the risks of the movement. Others simply have the wrong idea as to how it should be performed. Here’s a primer on what you should know.

There’s a misconception that the stiff-legged deadlift is dangerous to the knee joint. You’ll hear people say that you should never perform a movement that requires locking out your knees. Nonsense. To understand why, a little applied anatomy is in order. Although people tend to think of the knee joint (i.e. tibiofemoral joint) as a hinge joint, this is only partially true. In actuality, it’s a modified hinge joint (in geek speak, it’s technically classified as a trochoginglymus joint) given that a small amount of internal and external rotation takes place during flexion/extension. Specifically, when the knee begins to flex from a fully extended position, the tibia internally rotates to “unlock” the joint. During extension, the tibia then externally rotates to “screw home” so that the knee can fully lock out. This mechanism is necessary to achieve proper alignment of the tibial and femoral condyles. And herein lies the rub. Knee flexion is associated with rotation while there is no appreciable rotation of the knee during extension. Given that increased mobility results in decreased stability, which do you think is the more stable position? Full extension, of course. This is supported by in vivo (i.e. in the living) human research which shows that that anterior/posterior laxity of the knee is greatest at 20 degrees and tightest at lock out (Markolf et al. 1978). Bottom line: There is no detriment to locking out the knees when performing the stiff-legged deadlift.

There actually is a potential benefit to keeping the legs straight. You see, the hamstrings are a biarticular muscle, meaning they span two joints: the hip and the knee. By keeping the knees straight, the hamstrings remain in a fully lengthened position. Why is this important? Well, studies show that muscle force is optimized when a two-joint muscle is stretched at one end while acted upon at the other. This seems to be particularly important to an element called titin, which has been shown to act as a mechano-sensor for anabolic signaling. Thus, if your goal is to maximize hamstrings development, the straight-legged version will tend to heighten activity in this musculature. As an aside, there is reason why you generally shouldn’t lock the knees during performance of multi-joint lower body exercises like the squat as this diminishes constant muscular tension, but this is a topic for a different day.

Another issue with the stiff legged deadlift involves performance. Namely, I all-too-often see lifters get up onto an elevated platform or box so they can stretch down to the floor. Unfortunately, this extra range of motion generally occurs by flexing the spine. Problem is, this can place an extreme amount of undue stress on the discs, potentially leading to injury. Realize that the stiff-legged deadlift is a hip extension movement designed to target the glutes and hamstrings. Hopefully you know that the glutes and hams do not attach to the spine, so spinal movement will have zero effect on activation of these muscles! Bottom line: Bend only as far as your hips will allow. In most people, this generally means you won’t lower the bar much past your knees. You’ll feel an intense stretch in the hamstrings and this will be the limiting aspect to how far down you can go.

As far as performance, here are a few important cueing tips. First, always maintain a neutral lumbar/thoracic spine. To facilitate this posture, keep your head up throughout the move. I encourage lifters to see themselves in the mirror at all times (a tip I learned from the late, great Mel Siff). As soon as your head drops, your spine will reflexively tend to round. I’ve heard some coaches say that keeping the neck slightly hyperextended is problematic, but there is no evidence this is the case. In almost two decades of training clients, I’ve never had anyone complain of neck pain and, most importantly, no one has ever injured their lower back during performance. Second, try to push your butt backward as you descend. This will maximize activation of the hip extensors. Finally, actively squeeze your glutes at the top of the movement. The idea is to generate a powerful contraction that maximizes muscle activation in this position.

Here is a video explaining performance of the exercise. Enjoy!

embedded by Embedded Video

Reference

Markolf KL, Graff-Radford A, Amstutz HC. In vivo knee stability. A quantitative assessment using an instrumented clinical testing apparatus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978 Jul;60(5):664-74.

4 Comments

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)

Hi

You mentioned in the first part of the article to lock the knees out.

On the video the lady slightly bends it.

John

Comment by john — May 7, 2012 @ 7:11 pm

Hey John:

There is nothing wrong with having a very slight bend to the knee. The difference in hamstring length here would be minimal.

Comment by Brad — May 8, 2012 @ 7:04 am

As always Brad, great stuff. Providing factual info when fictional seems to dominate.

Comment by Jeff Harrison — May 10, 2012 @ 11:09 am

Wow, this is so timely Brad. I was involved in a two-day discussion with fellow trainers and clients regarding this just yesterday. I was poised to email you with questions. The debate wasn’t over concern for the knees as much as risk to the lower lumbar spine. Clients were bending their knees to reach the floor wherein I had suggested straightening the knees and lowering only as much as a flat or slightly arch back would allow. They directed me to various articles and illustrations recommending considerable flexion in the knees to allow the participant to touch the weight to the floor. From a practical point this made little sense to me since clearly there is greater hamstring activation with extended legs. Your article is greatly appreciated.

Comment by Charles Donahue — June 1, 2012 @ 4:38 pm